“I usually find chaotic people very enjoyable”

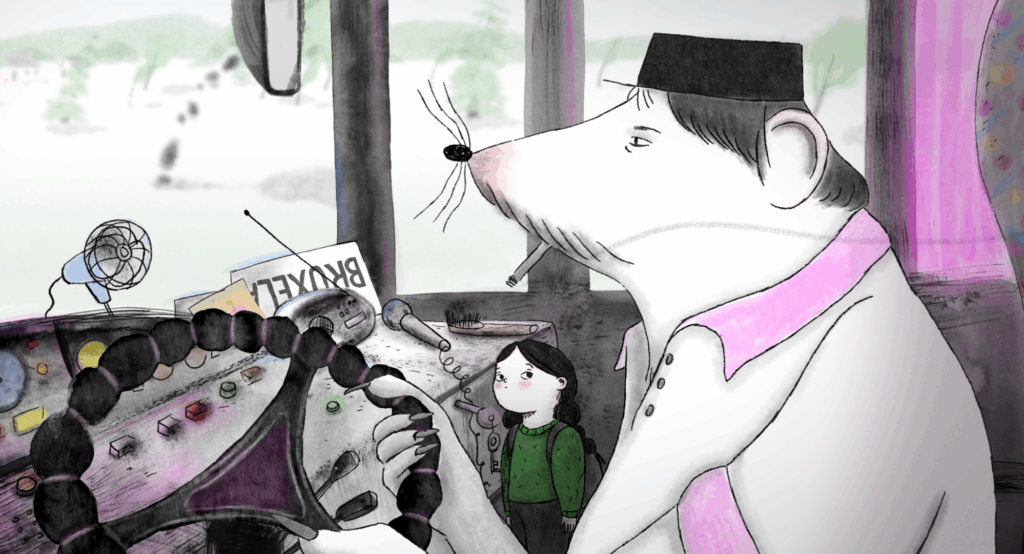

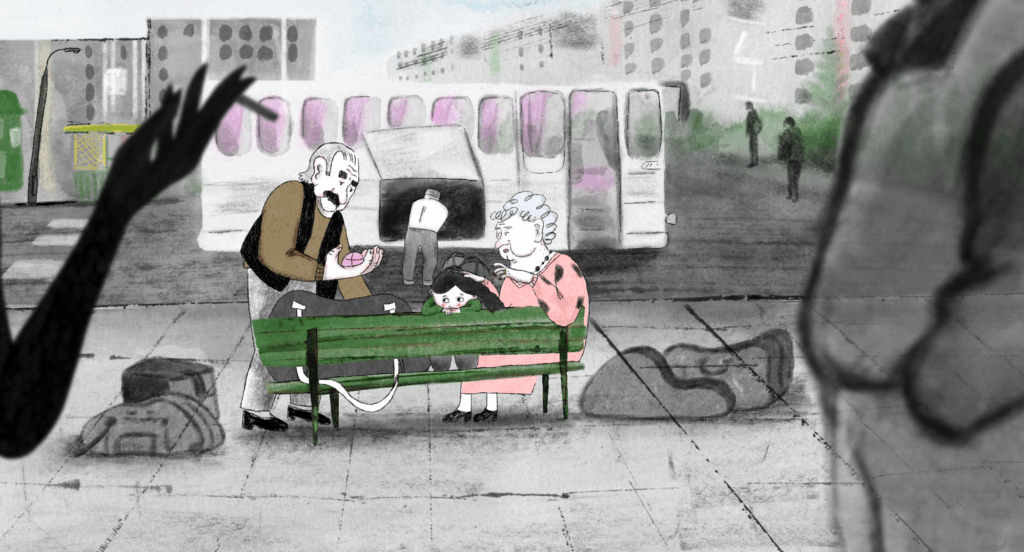

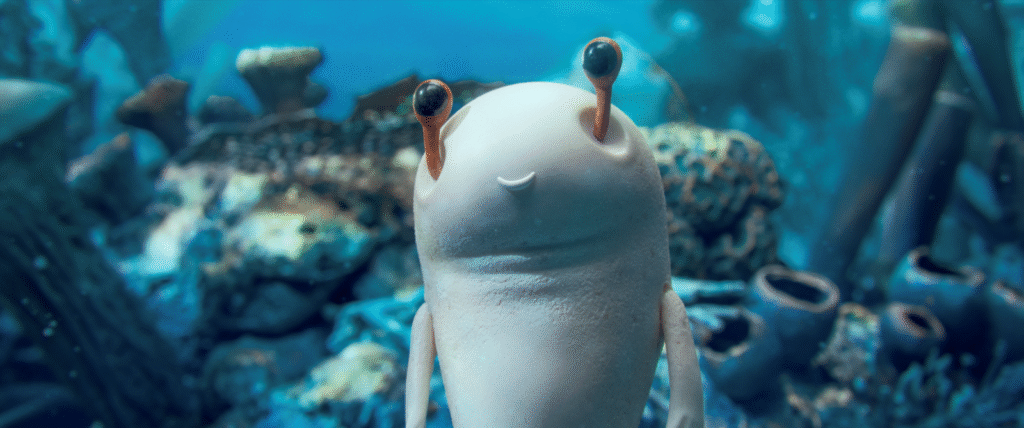

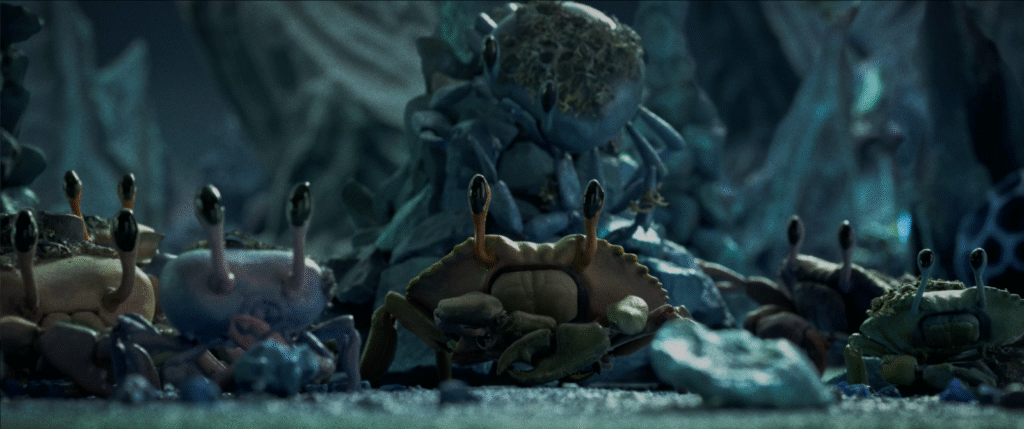

The life of 12-year-old Olivia is turned upside down overnight, now that she must learn to look after her younger brother. Fortunately, she gets help from her cheerful neighbours. Together, they turn every task into a game and every day into an unforgettable moment.

OLIVIA AND THE INVISIBLE EARTHQUAKE focuses on a fascinating group of children in the suburbs of Barcelona. The monsters they battle are the everyday problems of people struggling to keep their heads above water in uncertain times. If the film has a fairy-tale quality, it is to be found in friendship and solidarity among families and ‘kids from the block’. This Spanish co-production, which received a nomination for the ECFA Awards at the AleKino! festival, is the successful result of a quest to strike a balance between stylish design and a limited budget. That’s what Assistant Director Dorien Schetz tells us.

You are the one to define the scope of our conversation. As Assistant Director, I don’t know exactly what your responsibilities are.

Dorien Schetz: The story of the film, the design, and the sets are already fixed when I become involved in a project. My job is to supervise the organisation, and I prefer to do that for stop-motion films. That’s what I’ve been doing throughout my entire professional career, first at the Beast Animation stop-motion studio, and then on the sets of SAUVAGES (Claude Barras) and OLIVIA. I don’t choose projects based on content, but on the technique used.

How much stop-motion is OLIVIA AND THE INVISIBLE EARTHQUAKE?

Schetz: 100% stop-motion!

I don’t think so! I saw a bit of shadow play, I saw sand animation…

Schetz: It’s not 100% puppet animation, but stop-motion is about bringing dead objects to life. Like sand! Mama Fatou’s roots are beautifully illustrated in a piece of sand animation with a leopard and an African village. We had César Diaz on our team, one of my favourite animators and an absolute master of sand animation. It would be a shame not to use that skill in the film. That shadow play was filmed on set with transparent paper and then animated in stop-motion. The puppets and sets are real… You find stop-motion in many different forms.

Without too many technical gadgets.

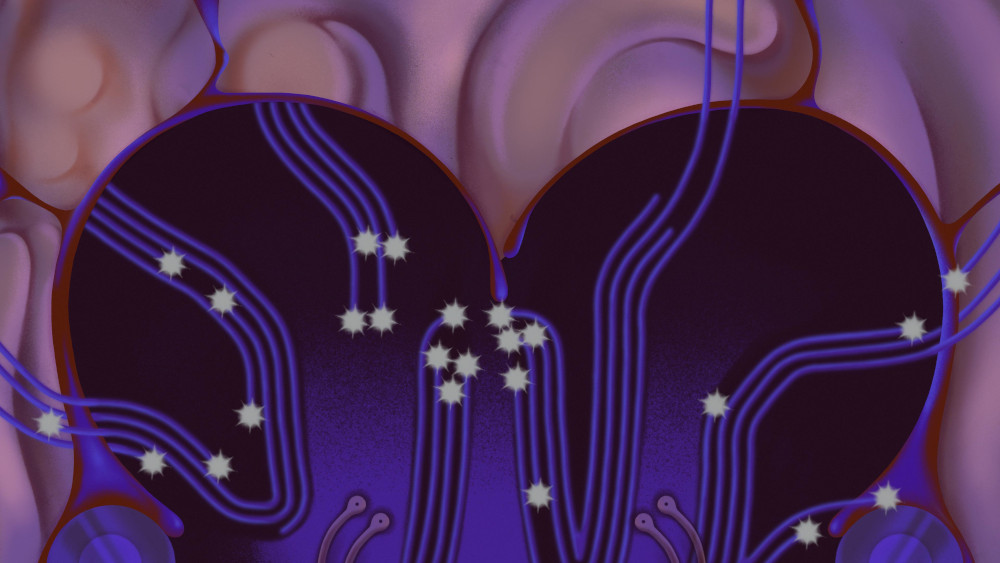

Schetz: This is a European low-budget film, but within our limited budget, the whole team has created something beautiful, purely artisanal, and with minimal post-production. The scene in which Olivia ends up in a dream world was created entirely by hand: the lighting was prepared, the effects were set up by the lighting team, and the animation was done layer by layer. In Barcelona, there is a brand of lightly sparkling water that is sold in bottles with a special relief pattern. The camera team used this to create a lighting effect. You can also do this with a lens that costs €10,000, but we did it with a bottle. Or we animated a candle flame with papier-mache on a flat plate, manually, frame by frame.

There is a striking shot in which we look through the camera of a mobile phone, and the hands are enlarged to fill the entire screen. They are so delicately made, with dirty edges under the nails.

Schetz: Hands are madness! I’ve never seen such perfect miniature hands, so delicate. They broke easily, so people on the team were constantly busy making hands.

The film is set in Barcelona. How am I supposed to know? The location is never mentioned.

Schetz: It can’t be anywhere else but Barcelona. You can tell from every detail: the pavements, the bollards in the street, the lampposts, the architecture of the houses. The set design team did a fantastic job. They even smuggled those flowered Flor de Barcelona tiles into the film.

From now on, my favourite place in Barcelona is Calle Futur 33, the street corner that is often shown in the film. Sometimes with people around, sometimes deserted…

Schetz: That’s a brilliant example of the work of our amazing team. Despite the limited budget, they got the most out of it. The result is stunning. Look at all those details: posters on the walls, notes with telephone numbers, a message about a runaway cat, the classic ACAB graffiti… Everything is there! The sets were made in Valencia. When they were delivered to Barcelona, we stood there staring with our mouths open. It was mind-blowing! The largest set was the street map, which was about 60 square metres. And that was just one of twelve! You can keep an interior set small, but as soon as you go outside, the size grows exponentially.

Depending on the time of day, the horizon changes colour beautifully, with shades of orange and purple.

Schetz: Credit for this goes to the camera and lighting team, who chose the right lighting mood for each sequence, as directed by DoP Isabel de la Torre. The director determines what time of day the scene takes place and what the weather conditions are like. Then the team gets to work creating the right atmosphere, which they maintain throughout the entire sequence, so that the sun is in the same place and the shadows fall correctly.

You’ve already passed on my compliments to someone else three times. Is there anything I can say that might be a compliment to you?

Schetz: That the film was finished on time. I moved to Barcelona in January, the shoot was due to start in April, and we had to be ready by the end of December. I knew in advance: we have 8 months of animation in 12 to 14 studios, 8 animators, 12 Olivia dolls, 10 Tims, 5 Lamines, 3 Vanessas, 2 Kikis, 5 mothers, and one Superspunk. We have to shoot so many seconds in so many sets… You have to get all the teams – set, puppets, camera, animation, direction, production, rigging, and post-production – to work together without everything exploding. And if something goes wrong, e.g. a puppet breaks, you have to anticipate very quickly. I have to make the perfect puzzle out of all those elements within a certain time limit. I succeeded in doing that, and I’m quite proud of it.

How does the assistant director relate to the director in the organisational chart?

Schetz: My main task is to take care of all the practical stuff, so that the director only has to think about the creative aspect. Which animator will make which shot with which puppet? It’s all planned out! That allows the director to concentrate fully on the emotions or the action in that shot. I do this job because I am frighteningly well organised. And because I love animated films, and many people in that sector are less well-organised. So I can help them. I don’t mind being surrounded by a bunch of chaotic people. I usually find chaotic people very enjoyable, and they are grateful for someone like me. We complement each other.

You made an interesting choice for the dolls’ basic hair.

Schetz: It’s usually wool, stiffened with iron wire, so that some hairs are still movable. The choice of material is determined by the available time and budget, in consultation with the director and the puppet designer. If the choice of material makes the animators’ work too difficult, it puts the brake on the number of seconds you can deliver per day.

If I were to ask you a similar question about the eyes, I would probably get the same answer.

Schetz: It is always the result of artistic and budgetary choices. You choose expressive eyes, but you also have to be able to work with them easily. The most difficult thing about Olivia was her glasses. They make her eyes difficult for the animators to handle, especially because we wanted to adapt the eyelids in every position. You see those animators fiddling with eyelids behind those glasses with a small stick, and then I’m glad I’m not an animator. Last year, on the set of SAUVAGES, all the characters had super-large eyes. That’s not only an artistic choice, but also a practical one, because it allows you to work faster.

The film features a few remarkable fantasy scenes, including a particularly striking one in which blue whales appear. Do these fit into the overall picture seamlessly, or do you need to develop a separate design for them?

Schetz: A shot in which they play Eskimo is much more complex than two characters simply talking, because you are working in different layers: the northern lights are one layer, the iceberg, the wavy water, the whale, the dolls… We estimate about four seconds of animation per day, but here you have to calculate four seconds for each of the five layers, so you’re working five times as long. What’s more, the whale was built on a small scale so that it wouldn’t be too unwieldy. It’s animated on green key so that it can be scaled afterwards.

The co-production line-up looks quite interesting, with Chile joining the usual suspects.

Schetz: That’s not so strange. No European country can produce a feature-length animated film on its own. Such a film is, by definition, an international co-production. Spain and Chile couldn’t secure the financing. So France, Belgium and, in the end, Switzerland joined in.

And completed the film in eight months! Isn’t that incredibly fast?

Schetz: We did SAUVAGES in six months! That’s fast. But OLIVIA did stay within the time frame, at an average of 3.2 seconds per animator per day.

Because you strictly ensured that everyone met their quota!

Schetz: Indeed, strictly but fairly.

Gert Hermans

La Rosa: That song is sung in a strong Neapolitan dialect. This ‘Neomelodica Napoletana’ music is very popular in that neighbourhood, but we couldn’t understand the lyrics. We still don’t know exactly what the song is about, but the only words we could get – ‘

La Rosa: That song is sung in a strong Neapolitan dialect. This ‘Neomelodica Napoletana’ music is very popular in that neighbourhood, but we couldn’t understand the lyrics. We still don’t know exactly what the song is about, but the only words we could get – ‘

Can you do an elevator pitch for Benshi?

Can you do an elevator pitch for Benshi?

Fran has a striking, radiant effect in her eyes.

Fran has a striking, radiant effect in her eyes.

Asensio: That is what made me fall in love with Alessandra the first time I saw her on tape. We asked all candidates to improvise around a few questions and clues we gave them. She was the only one who would not answer right away; she took a minute to process the question, trying to understand exactly what we wanted from her, and then gave us an eloquent answer. Not to impress us, but just because she is like that. She has a great intuition. Let us hope she never takes acting lessons! Keep your intuition intact and remain curious about the world; that’s the best acting class you can get.

Asensio: That is what made me fall in love with Alessandra the first time I saw her on tape. We asked all candidates to improvise around a few questions and clues we gave them. She was the only one who would not answer right away; she took a minute to process the question, trying to understand exactly what we wanted from her, and then gave us an eloquent answer. Not to impress us, but just because she is like that. She has a great intuition. Let us hope she never takes acting lessons! Keep your intuition intact and remain curious about the world; that’s the best acting class you can get.